PRE-SETTLEMENT GLEBE

The Glebe and Forest Lodge region was long occupied by the Gadigal and Wangal people. Back then Blackwattle Bay and Rozelle Bay had meandering shorelines. There were extensive mudflats, with mangrove forests, saltmarshes and brackish swamps fed by freshwater streams where Wentworth Park and Harold Park are today. The Bays provided a plentiful supply of fish and shellfish. The women fished from bark canoes called nowies using shellfish hooks and lines from the inner bark of trees, while the men speared fish from the shore. The Bays provided bream, flathead, mud and rock oysters, mussels, cockles, crabs, octopus and turtles.

Glebe lies on a ridge of Hawkesbury sandstone shale. The great Turpentine-Ironbark forest of pre-settlement Sydney grew along that ridge. The grey ironbark (Eucalyptus paniculata) on the grounds of St Johns Anglican Church, on the corner of Glebe Point and St Johns Roads, is arguably the only remnant of the old forest in Glebe.

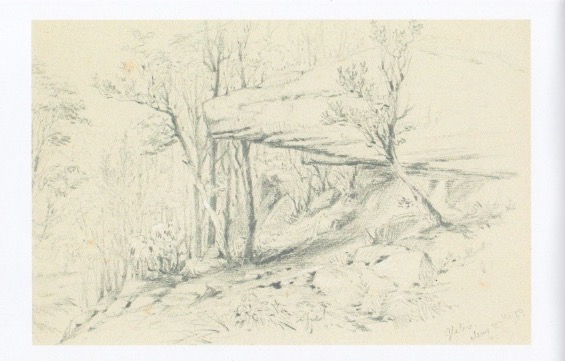

Botanists Doug Benson and Jocelyn Howell wrote: “On the more rugged Hawkesbury sandstone landforms – the harbourside suburbs of Glebe and Balmain – would have been typical Sydney sandstone open forest, with trees of smooth-barked apple (Angophora costata)and Sydney peppermint (E. piperita). The species present would have been similar to bushland found today on the nearby northern side of the harbour, such as at Balls Head and Berry Island” They state that the 1859 pencil sketch by Conrad Martens “captures the nature of the steep wooded slopes and overhanging sandstone rock ledges that were to disappear during the next 40 years under the terrace houses of Glebe”. (1)

Conrad Martens, Glebe May 17, 1859, Album of Pencil Sketches, State Library of NSW

Swamp oaks or casuarinas grew near the water, grey mangroves grew in the intertidal zones and Blackwattles grew along Blackwattle Creek. (The Blackwattle, Callicoma serratifolia, is not a true wattle or acacia. It was called a wattle because it was the first tree used in early Sydney to build wattle and daub huts.)

Blackwattle Creek, which flowed from swampy lands that are now in the grounds of the University of Sydney, was a source of fresh water for Sydney’s Aboriginal people, and a place for fishing and other activities.

Paul Irish and Tamike Goward write: ““During the early decades of European settlement the creek was located at the edge of town, but by the middle of the 19th century, the course of the creek was highly modified and densely inhabited by some of Sydney’s poorest residents.

Despite these impacts, some archaeological traces of Aboriginal people living along the creek have survived. The most substantial evidence has been found at an Aboriginal campsite located on the original banks of the swamp at the head of Blackwattle Bay.

While these sites only give us a glimpse of how Aboriginal people used Blackwattle Creek, we can at least see that they were there, and that they continued to use the area after Europeans arrived in Sydney. The sites are also a reminder that physical evidence of this kind still survives in the city, despite two centuries of intense European activity.” (2)

There is also some evidence of Aboriginal middens – the remains of shellfish – in the narrow strip of remnant salt marsh fringing the lower parts of Johnstons Creek. The ark cockle, scallop and Sydney rock oyster and mud welk found there indicate that is was a fertile swamp and a rich source of food for the first inhabitants.

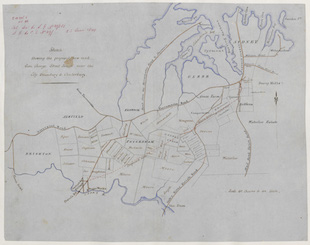

Series: NRS 13886 Surveyor General’s Sketch books. Cumberland County Petersham 23/06/1849

BLACKWATTLE BAY

Blackwattle Bay was one of the earliest boundaries of settlement, and was soon populated with small industry, including flour milling, animal processing such as tanneries, brick manufacturing and breweries, along with housing.

A bridge crossed the Bay where Bridge Road is now, and travellers were charged two pence (2d) to walk across it, 3d for horse and rider and 9d for a two-horse chaise. In those pre-sewage days Blackwattle Bay soon became heavily polluted and unsanitary. Stormwater, industrial waste and untreated sewage ended up in the Bay.

The mangrove forest area, also known as Blackwattle Swamp, was filled in between 1876 and 1880. Reclaimed land was considered unsuitable for building on, and became sporting facilities and open ground, and as a result Glebe had three sporting facilities on formerly swampy ground: Wentworth Park (1882); Harold Park (1890); and Jubilee Oval (1910). Harold Park was later built on.

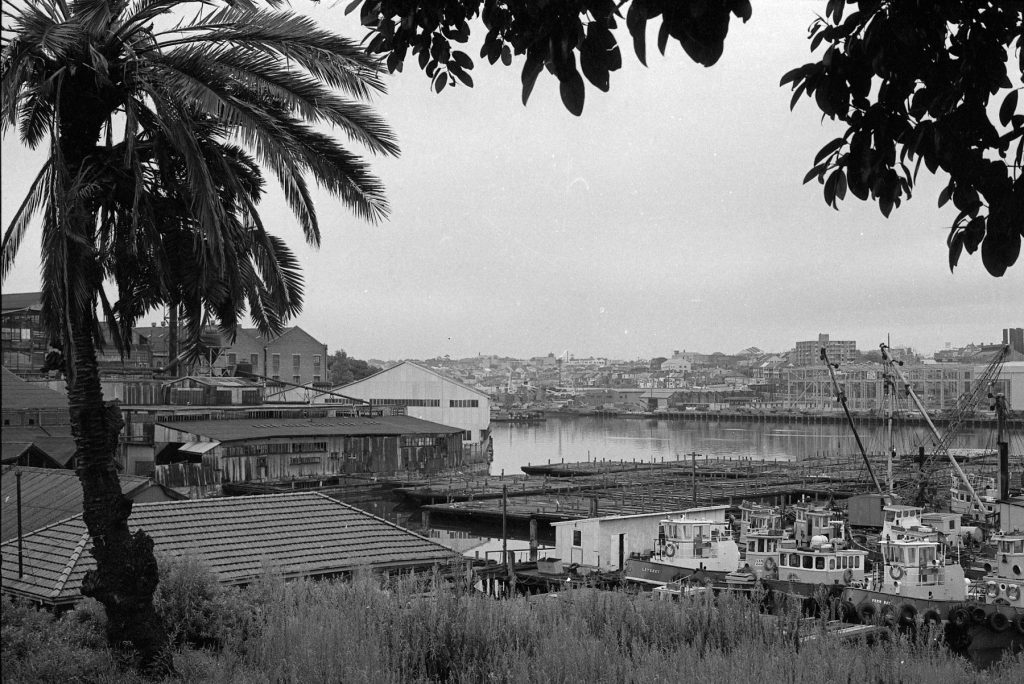

In 1880 there were 30 manufacturing works in Glebe, including coach and wagon works, joineries, sawmills, furniture workshops, brass and iron foundries and a pottery. The timber industry, which relied on moving timber by boat and barge, became a strong presence along the waterfront in the first half of the twentieth century. By 1944 there were 156 factories in the area. (3)

Blackwattle Bay and Glebe Foreshore 1970 Max Solling Collection

TIMBERYARDS

In 1883 the Auckland Timber Company opened a timber yard on what is now Sydney Secondary College Blackwattle Campus. It was later sold to George Hudson & Son, who advertised the site as the largest timber mill in Australasia.

Vanderfield and Reid set up on a large site further down the Bay, south and east of Leichhardt Street, in 1913. Hardy Brothers had timber drying sheds at the end of Glebe Point Road. Sylvester Stride’s ship breaking yards, and the little tugs of Harbour Lighterage (a lighter is a small boat that transfers loads, a big business in the bays) were off Oxley Street.

There were more timber businesses along Federal Road and around the Bay to Annandale: Langdon and Langdon; National Plywood; and Sydney Sawmilling.

When The Glebe Society was founded in 1969, Blackwattle and Rozelle Bays were still working waterfronts. The only public access to the Bays was Marine Reserve (later renamed after Pope Paul VI) at the end of Glebe Point Road.

The area began to deindustrialise, and the Glebe Society was at the forefront, arguing that formerly industrial waterfrontage should be made into parkland and opened up to the public. Residents lobbied and planted and cared for trees in areas they hoped would become parkland.

Blackwattle Bay, SRC 24125 Bernard Smith collection, City of Sydney archives

THE FORESHORE WALK

The official waterfront walk, from Bridge Road to Chapman Road, was finally completed in 2014. It extends 2.2 kilometres through four parks: Blackwattle Bay; Bicentennial; Jubilee; and Federal Parks. Over 400 trees and 8,500 shrubs, herbs and grasses have been planted along it.

Federal Park is the oldest. Dedicated on reclaimed land in 1899, it was named Federal Park in 1902 to commemorate Federation the previous year. It spanned both sides of Johnstons Creek Canal. In 1909 Glebe’s side was renamed Jubilee Park to mark the fiftieth anniversary of Glebe. Jubilee Park was extended to Victoria Road in 1911.

Bicentennial Park Stage 1, east of the canal, opened in 1988, hence the name. Stage 2, west of the canal, opened in 1995. Blackwattle Bay Park, along the Blackwattle Bay foreshore, was completed in 1983. The final stage of the walk, along the foreshore of Blackwattle Secondary College, was completed in 2014.

The interlinked parks are considered to have high biodiversity value due to the relatively large size of the area covered, several bush restoration sites, the endangered coastal saltmarsh communities, the only mangrove forest in the City of Sydney, the high diversity of flora with over 100 locally indigenous species, and the diverse habitat for fauna which included sandstone outcrops and retaining walls, a small freshwater pond and freshwater seepages.

The section from Bridge Road is the most recently completed part of the walk. For over a century the timber yard, George Hudson & Sons covered the entire site with stores and mills. Its chimney was visible for some distance, and its barges were moored in Blackwattle Bay.

The company went into liquidation in 1974 and the land was acquired by the Department of Education. Glebe High School, now Sydney Secondary College Blackwattle Campus, opened on this site in 1971. The walk in front of the campus was opened in 2014. The seawall has been designed to include suitable habitats for marine species.

The foreshore walk continues walk past the Glebe Rowing Club, established in July 1879. It is the third oldest rowing club on Sydney Harbour.

The path crosses Ferry Road. Before the bridge across Blackwattle Bay was built and the Bay was filled in, boatmen used to pick up passengers here who wanted to cross the Bay. The path then enters Blackwattle Park. This was one of the later additions to the walk, opening in 2007. It wasa container terminal, owned by John Fletchers. The site was purchased by Australand, and the area in front dedicated to parkland.

The incinerator, on the corner of Forsyth Street and Griffin Place is one of just two inter-war art deco-style Walter Burley Griffin incinerators to survive in Sydney. Itt operated between 1933 and 1949. The Glebe Society and the Walter Burley Griffin Society lobbied for it to be preserved. It was restored as meeting rooms in 2006. (4)

The Park at the end of Forsyth Street combined land from Australand’s development of the John Fletchers’ site with the old council depot site.

Former Glebe Society John Buckingham recalls: “Thankfully, at the old Fletchers’ Container Storage site and Council’s storage site, we gained a waterfront area commensurate with our desserts. The High School site too is a story on its own. While we don’t have complete free and open access, the alternative would have excluded us from the site whereas, as public land, Council has been able to negotiate access along the waterfront.”

Foreshore walk, Blackwattle Bay Park

A small corridor of lemon scented gums (Corymbia citriodora)has been planted between the incinerator and the apartment block facing the water along Griffin Place. Clean-barked and stately, lemon-scented gums were frequently used to line long country drives. The leaves, when crushed, smell like lemons.

The walk continues to Cook Street. John said: “The [waterfront walk] site on the southern side of Cook Street was settled in the Land and Environment Court. We were well prepared, expecting to gain a substantial strip along the waterfront but gaining a miserly strip. It is the one near-blot on the foreshore walk.”

The area from Cook Street was occupied by timber millers Vanderfield and Reid from 1913 until its sale to Parkes Development for home units in 1975.

The Glebe Society and the Sydney Foreshores Committee campaigned for the developer to dedicate part of the land for waterfront park. In 1979, Parkes Development handed Blackwattle Bay Park to Leichhardt Council, which Glebe then was under. The park was completed in 1983.

The main tree species planted were Casuarinas, Swamp Mahogany (Eucalyptus robusta)and other Eucalypt species, and several peppercorn trees (Shinus molle). Peppercorns are not natives, but were commonly planted around houses in the nineteenth century, and their berries are not actually pepper. The understorey was planted with Acacias, Banksias, Callicoma, Melaleucas, Grevilleas and Westringia. (5)

Alongside the waterfront path are swales planted with rushes that retain stormwater.

Hundreds of shrubs, grasses and groundcovers have been planted in the foreshore park, to improve the diversity of locally indigenous plants and create dense understorey habitat to encourage small birds. Some rock features have been installed to encourage lizards and invertebrates.

Bellevue, the house on the point, was built by William Jarrett in 1896. In 1920 it was turned over to industrial use. In the 1970s it became derelict, but after local lobbying it was purchased by Leichhardt Council. It was restored in 2006 by the City of Sydney, which took over Glebe in 2003.

THE GLEBE SOCIETY CAMPAIGN FOR BLACKWATTLE PARK

The campaign, which began in August 1978, combined lobbying of politicians, festivals and what was essentially guerrilla action.

Former Glebe Society President, John Buckingham wrote: “The campaign for Blackwattle Bay Park officially opened in August 1983. The campaign for Bicentennial Park was long, drawn out and full of intrigue and political conspiracy. Blackwattle Bay Park (and the rescue of Bellevue), by contrast, suddenly happened. It too had been part of our founding fathers’ plans, but the potential park site here did not involve politicians.

“When the massive site, bordered by Blackwattle Bay, Cook Street, Leichhardt and Oxley Streets and the older multi-storey developments on Cook and Leichhardt Streets, was bulldozed to make way for a new development, locals like Eric Gidney, Chris Hosking and Bob Armstrong kept a close eye on any activities on the site. They worked closely with Tony Larkum’s Glebe Society Management Committee,” John said.

THE GUERILLA ACTION

“A report of great significance advised when the site was cyclone-wired into two areas: the area away from the water, Parkes Developments’ Stage 1 of the development; and the waterfront area, their final stage. The locals and the Glebe Society saw their opportunity – turn the waterfront area into a quasi park,” he said.

“Simple landscape plans were drawn (the eventual professional ones by Stuart Pittendrigh for Parkes Developments and Leichhardt Council were infinitely better); Chris Hosking drew up plans for a viable use of Bellevue; and Tony Larkum and some cohorts somehow penetrated the fencing, planted trees on the site and watered them. We actually thought the site was ours!”

THE FESTIVALS

In October 1978 Eric Gidney wrote in The Glebe Society Bulletin: “Blackwattle Bay Park at the end of Leichhardt Street is one of our best bits of foreshore land. Back in August I formed the Waterfront Action Group to get things moving. The first activity was the Spring Festival, well attended (500 people) which triggered off a fair bit of media interest and resident participation.

“We’ve now built a barbeque, planted trees, cut the grass, cleaned up some of the rubbish… and we are ready for stage 2 this Saturday, October 7, the Election Dig.

We’ve come up with a plan, we’ve been given a 2 ton tip truck by Kennards just for the day, now all we need is your support – bring your muscles, pickaxes, spades,

seedlings, trees, kids, ideas, wheelbarrows, lunch etc. Help us prepare the site for the next great event, The Guy Fawkes Celebration on Sunday 5 November at 7 pm.”

The following month Eric reported: “The Guy Fawkes celebration at Blackwattle Bay Park was a great success despite the downpour. Up to 700 people came along for the performance and barbeque”. The entertainment was provided by the English Ancient Rites. “They organised the Punch and Judy, the dances, the mulled wine, the bonfire and the witch.”

The article concluded by warning the Guy Fawkes night might be the last community celebration there. “There are signs the bulldozers may move in at the end of this month…REMEMBER – Glebe is a foreshore suburb without a waterfront park. If you don’t act now the Blackwattle Bay Park may be gone for good.”

THE ACTION

John said the message went around by telephone, “ ‘The cyclone fence has been removed and there are bulldozers on the site!’ As was inevitable, the work was to begin on a weekday. Receiving the message in many circumstances were the wives at home looking after the babies. I’m proud to say [his wife] Deanne heeded the call, gathered the kids into the car and drove onto the site where the bulldozers were poised to join the others.

“The bulldozer drivers shut down their machines and contacted their union chiefs. No further work took place.

THE SUCCESS

The first Bulletin of 1979 was headlined: Stop Press! BLACKWATTLE BAY PARK, VICTORY AT LAST!

“Well, after several meetings and much negotiation with developers, council, State Government and unions, a compromise has been reached on the Blackwattle Bay Park. Paul Landa, Minister for Planning & Environment, told us that he didn’t have money for everybody who wanted a foreshore park.

However he would help us to negotiate with the developers. So, armed with this and a Green Ban imposed by the Building Trades Group, we proceeded to get together with Leichhardt Council and the developers and look at a way to provide the maximum size park with the minimum environmental impact from the proposed development.”

The result, while not all The Glebe Society had hoped for, was a reduction in the number of units, which were capped at three stories plus parking, and a waterfront park. (5, 6)

Coastal Banksia (Banksia integrifolia) Foreshore Walk

BIODIVERSITY VALUES

From the City of Sydney Urban Ecology Strategic Plan

The high biodiversity values of the Foreshore Walk and the associated parks, included Orphan School Creek, are due to the following:

- Relatively large size, incorporating several bush restoration sites;

- Relatively continuous area of open space from the Glebe Foreshore to Forest Lodge, a distance of 2.5 kilometres;

- Presence of a possible remnant tree representative of the critically endangered Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest community, near Orphan School Creek;

- Presence of the endangered Coastal Saltmarsh community, in Federal, Bicentennial and Jubilee Parks;

- Presence of the only patches of Mangrove Forest that occur within the LGA, on the Rozelle Bay foreshore;

- Presence of naturally occurring flora species that occur in association with sandstone outcrops;

- Very high flora species diversity (over 100 locally indigenous species recorded) as a result of bushland restoration works at numerous sites, mostly by volunteers from the Glebe Bushcare Group;

- Diverse fauna habitat features, including sandstone outcrops and retaining walls, a rocky modified creekline and other ground-level habitat features such as fallen timber, a small freshwater pond and freshwater seepages, structurally complex patches of locally indigenous vegetation, and intertidal habitats;

- The presence of one of only two known populations of both the Bar-sided Skink and Eastern Water Skink in the LGA;

- High potential to expand bush restoration works and increase the diversity of locally indigenous flora species, and to undertake fauna habitat enhancements;

- High potential to expand on planted elements of the endangered Swamp Oak Floodplain Forest community that are already present in the park, using shrubs and groundcovers of this community;

- The greatest potential to provide an almost continuous (albeit narrow) habitat corridor in the LGA, with connectivity to habitat areas in the Leichhardt LGA, and potential for connectivity to be established with sites at Pyrmont along the future Glebe Foreshore Walk extension, and new parks that will be created in this area in the future at Harold Park, the Hill and Crescent Land sites; and

- Potential for naturalisation of Johnstons Creek Canal, to not only improve habitat for Coastal Saltmarsh but also to benefit a range of estuarine fauna species, including wetland birds, fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Site constraints affecting the above biodiversity values include:

- The limited extent and poor condition of Coastal Saltmarsh along Johnstons Creek Canal due to the presence of self-sown Phoenix Palms;

- The narrow, linear nature of the potential corridor, since corridors of this type are of limited value to some priority fauna species;

- The occurrence of environmental weeds, particularly annuals and Chinese Hackberry Celtis sinensis; and

- Heavy use of the Glebe Foreshore Walk, Blackwattle Bay Park, Bicentennial Park, Jubilee Park, and Federal Park for recreational activities.

Aerial Photographic Survey 1949 Map 37, City of Sydney Archives

IN 1969 THERE WAS ONE FORESHORE PARK IN GLEBE

In 1969 the only foreshore park in Glebe was Pope Paul VI Park, at the end of Glebe Point Road. Very little of Glebe and Annandale were parkland: Glebe had only 40 per cent of the area of parkland that was considered adequate at the time, while Annandale had only 16 per cent.

Blackwattle Bay Park became the second link in the chain, when it was completed in 1983. Between Blackwattle Bay Park and Pope Paul VI Park the foreshore was still owned privately and by the State Government, and inaccessible to the public.

Beyond Pope Paul VI Park the Rozelle Bay waterfront was still occupied by a series of businesses on Maritime Board land. Federal Road ran between the waterfront businesses and Jubilee Park. It crossed Johnstons Creek over the Truss Bridge. The Annandale side of Johnstons creek was a timber yard.

Johnstons Creek was named after George Johnston of the NSW Corps. He was granted land on the other side of the creek, which he named Annandale, after his home town in Scotland.

The Creek originally spread across the valley, in the form of mudflats, estuarine wetlands and mangrove forest. The original shoreline can be traced around the edge of Jubilee and Federal Parks, past where the Tramsheds are today, across Harold Park.

Reclamation of the swamp land around the creek’s mouth began in 1886, creating the stormwater canal and the parklands on either side. A referendum rejected use of the land for industry only, and part of the reclaimed land was dedicated as parklands in 1899. It was named Federal Park in 1902 to commemorate the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901.

Johnstons Creek became a stormwater channel, andformed the boundary between Glebe and Annandale municipalities for over a century. Glebe’s section was renamed Jubilee Park in 1909 to mark 50 years of the municipality. Today both come under the City of Sydney Council; the western boundary is The Crescent.

Federal Road was closed in the 1980s and its route is now marked by paving and the replica Allan Truss pedestrian bridge across the canal.

Pope Paul VI reserve was formerly called Marine Reserve. There was a wharf at the end of Glebe Point Road and after Pope Paul VI disembarked from a launch there, to visit the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children in Camperdown in 1970, it was renamed after him. Neither the wharf, nor the Hospital, are still there.

Glebe, SRC 24123 Bernard Smith Collection, City of Sydney Archives

THE OLDEST TREES IN JUBILEE PARK

The oldest plantings in Jubilee were undertaken in the 1890s.

The formal avenue of 26 Canary Island Date, or Phoenix, Palms located immediately east of the oval, supported by an associated row planting of 13 palms, is believed to have been planted in 1935. The Canary Island Palm, with its drought tolerance and uniform and dramatic growth pattern, was often used in early commemorative parkland and civic landscapes, particularly in the Inter-war Period between 1915 and 1940.

However, a number of these plantings, particularly in Centennial Park, have recently been affected by a soil fungal pathogen, known commonly as Fusarium wilt. Fusarium wilt has been found it at least one of the Jubilee Park palms, and the remainder are expected to eventually fall victim to the disease for which there is currently no treatment.

The City of Sydney states: “The avenue of Canary Island Date Palms (Phoenix canariensis) is one of the most outstanding examples of civic planting using this species in the Sydney metropolitan area. This formal avenue (26 palms) and associated row planting (13 palms) has group significance at the City/ LGA [Local Government Area] level in terms of its commemorative, social, aesthetic and visual values. (9)

The creation of Bicentennial Park was a huge step towards the overriding plan for a foreshore walk from Bridge Road to Annandale. But in 1988, between Bicentennial Park and Blackwattle Bay Park, there was still a series of privately-owned waterfront properties blocking progress.

Over the decades the waterfrontage belonging to the privately held houses along Oxley, Stewart and Mary Street was transferred to council for the foreshore walk.

Sylvester Stride’s former ship-breaking yards are marked by one of his cranes, which remained to commemorate the site’s maritime industrial history. The small park opposite the end of Leichhardt Street was won in an earlier campaign.

The acquisition of these properties began under Leichhardt Council, and the process speeded up when Glebe was transferred to the comparatively wealthy City of Sydney in May 2003. John Buckingham said: “The accelerated pace began under Lucy Turnbull, who came on our waterfront walk early in her short stint as [City of Sydney] mayor. She recognised the need to complete the transfer of the Anchorage waterfront site [the land behind 451 Glebe Point Road] quickly, and the need to restore Bellevue which, by now, despite the holding operation 25 years ago, was in a desperate state of disrepair. The next council, under Clover Moore, really got on with the job. She sees our foreshore walk as part of a foreshore walk right around the harbour’s southern shore contained within City of Sydney Council’s borders.”

Harbour Lighterage, below 18 Oxley Street and now called Bridgewater, had a wharf and a collection of tugs. (Lighters are small boats that ferry goods from larger boats to shore). The transfer was settled Land and Environment Court. “We did not get what we wanted but the result is better than we might have expected,” John said.

It took decades to obtain the waterfrontage to The Anchorage, at 451 Glebe Point Road. Fifty years ago there was an old house and a derelict tennis court up the top, and the remains of a harbour pool down below. In 1974 the house was demolished and construction of the current buildings began. The waterfront level was left vacant, accessed by a steel ladder down the cliff. For 25 years Leichhardt Council’s approaches to purchase the waterfrontage were refused, but the City of Sydney proved more persuasive. (10)

In the 1960s there were a series of warehouses at the end of Glebe Point Road, where the Pavilions now stands, owned by Hardy Brothers. By the late 1970s their old timber drying sheds were occupied by many creative types, including artists and boat builders. That building was sold to home unit developers, with the waterfront land given to council for park land being a condition of rezoning. The waterfront walk from Blackwattle Bay to Pope Paul VI Park was completed in 2005.

Parramatta Green Wattle (Acacia parramattensis) Foreshore walk

THE BATTLE FOR BICENTENNIAL PARK

By John Buckingham

When [then-Premier] Bob Carr came to one of the park functions in 1988 during the development of Bicentennial Park Stage 1, he likened our campaign for waterfront open space to the Wars of the Roses – Bob’s a history, not a movie, buff! He was, no doubt, conscious of the intrigue, conspiracy and mayhem conducted along the way to our gaining this wonderful park.

The campaign for Bicentennial Park Stage 1 (the Glebe side) lasted 20 years. The campaign for Stage 2 (the Annandale side) was to take a little longer. [In 1969] Federal Road continued from Glebe Point Road straight through what is now the centre of Bicentennial Park over Johnston Creek Canal, by what was then the road bridge, to Minogue Crescent.

Between Federal Road and Rozelle Bay there were unused/misused (previously waterfront industrial) sites. At the bridge there was the long-since-abandoned Purr Pull petrol storage site. From there to Pope Paul VI Park there were sites that in an earlier era had been served by lighters and had been legitimate waterfront timber millers: raw product in by water; finished product out by water.

By 1969 some of these sites were abandoned. Others were used as timber storage or as non-waterfront industrial timber workshops – in by truck, out by truck. From its inception, the Glebe Society has had a policy of supporting legitimate small scale waterfront industry in our bays, but these sites had ceased to function within that policy.

During the first fifteen years of our campaign we had no formalised plan for the potential park. We had vague ideas of what it should look like, but our emphasis was on trying to have the politicians recognise the logic of our arguments – these sites were not being used for their zoned purpose, so they should be handed over for open space.

It was the coming of the Evan Jones/Nick O’Neill [Leichhardt] council, the approaching Bicentenary and real plans to take to the politicians that gave us our boost. Now they were actively interested. Leichhardt Council formed a Bicentennial Committee, and as Glebe Society representative, Neil Macindoe’s job was to make sure the Bicentennial Park remained at the top of the list for the next four years.

There were more trials and tribulations along the way: the State government’s attempt to offer Stage 1 if Stage 2 were to become a marina; squatters taking over some of the buildings after the decision had been taken by the government to develop the park and asbestos discovered prior to demolition.” (11)

Note: When Bicentennial Park was opened in 1988, John points out the park was not complete because the fountain from the original plan had not been built. That is still the case today.

Flowerpot, Blackwattle Bay

BRINGING BACK MARINE BIODIVERSITY

Both Blackwattle and Rozelle Bays are blind-ending bays that experience very little flushing. Add to that the early days when raw sewage and industrial waste flowed freely into the bays, the destruction of the mangrove forests and the replacement of the entire natural waterfront with sea walls, and the result is dramatically reduced biodiversity.

In 2006 commercial fishing was banned in Sydney Harbour. While recreational fishing has not been banned, the Department of Primary Industries advises that fish and crustaceans caught west of Sydney Harbour Bridge, which includes the Bays, should not be eaten. (12)

Fishing blogs report that bream, whiting, chopper tailor, flathead, mullet, leatherjacket and jewfish have been caught in Rozelle Bay.

Rebecca Morris, formerly from the Coastal and Marine Ecosystems Group at the University of Sydney, has studied the marine life of the Bays. Rebecca, along with Associate Professor Ross Coleman, set up a ‘green engineering’ project in the Bays, a series of flowerpots attached to the sea walls.

Ross points out that the pre-European Harbour consisted of a mixture of rocky headlands, sandy beaches, salt marshes and mangrove forests. That has replaced by seawalls around the Bays, with the exception of two small areas of restored mangroves. Seawalls lack the myriad nooks and crannies marine animals need for habitat.

The flowerpot is a half pot that is attached to a seawall, that provides missing habitat, with cameras installed to observe the species. The flowerpot project received a grant from the City of Sydney. The project found that before the flowerpots was installed, there were maybe nine species. Afterinstallation 40 species were observed, with 28 species in the flowerpots, including algae, snails and starfish, and small fish at high tide. (13)

At the time of settlement, Sydney Harbour had huge oyster reefs, so large ships had to navigate around them. Oyster shells have a high lime content, and were harvested in enormous quantities make mortar for early buildings. Aboriginal middens were also raided for the shells. Fragments of shell can be seen in the mortar of some of Glebe’s oldest buildings.

As a result most of Sydney’s oyster beds were wiped out, and the native flat oyster, Ostrea angasiwas eliminated. The Sydney Institute of Marine Science is working to restore the lost oyster reefs, and to bring back the angasi species. Their first experimental site is in Botany Bay, but they are also looking for safe sites in Sydney Harbour. Oysters clean up the water, filtering out excess nutrients and heavy metals. The reefs provide habitat for many sea creatures, like snails and crabs, which in turn attract fish. Oyster reefs can also act as a buffer against wave damage. (14)

Shells in mortar, Glebe

THE POLLUTED BAYS

Blackwattle and Rozelle Bays are amongst the most polluted in the Harbour.

In 2015 a study assessing pollution in Sydney Harbour gave Blackwattle and Rozelle Bays, along with Iron Cove and Homebush Bays, the lowest grade.

The pollution is due to industrial activity, particularly in the early days of settlement, and more recently stormwater pollution, sewage overflows and leachate from contaminated land. The heavy metal pollution of Blackwattle Bay began in the decade after 1866, when coppersmiths, paint manufacturers, the first Sydney Gasworks, engineering works, sawmills, breweries, a distillery, coal depots, and a boiling down works were established. The biggest polluter was the Glebe Island abattoir. Glebe was unsewered until the 1890s, and prior to that sewage flowed into the Bay.

Although metal contamination in the sediment of the Bays has declined over the past few decades, again the Bays were among the worst polluted. The study measured copper, lead and zinc. About 20 per cent of those metals found in Sydney Harbour were found in just four bays, including Blackwattle and Rozelle Bays.

The most significant contributor to current pollution is stormwater, which can contain arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, nickel, lead and zinc. The copper found in the Bays nearly always exceeds the guidelines; zinc frequently, and arsenic, chromium and lead, occasionally exceed them. (15)

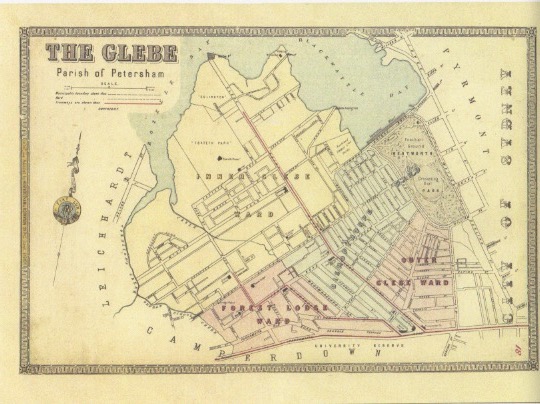

Atlas of the Suburbs of Sydney – Glebe 1886-88 Higinbotham & Robinson City of Sydney Archives

JOHNSTONS CREEK

The Johnstons Creek of today, a mostly straight concreted channel, is very different from that of pre-settlement times. Rozelle Bay used to extend inland, covering what are now Bicentennial, Jubilee, Federal and Harold Parks. There were mangrove forests, rugged rocks, saltmarshes and brackish swamps and an intertidal zone of sand and mud.

The area was distained as a swamp, and it was polluted from storm water, industrial waste and sewage that flowed into it. Efforts to reclaim it, to fill it in began in 1886. The naturally meandering Johnstons Creek was straightened and turned into a storm water channel in 1898. It was one of the first stormwater drains constructed in Sydney.

The reclaimed land was dedicated as a park in 1899, and in 1902 it was named Federal Park to commemorate the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901. The Creek became the dividing line between Glebe and Annandale, and in 1909 the park on the Glebe side was named Jubilee Park to celebrate Glebe’s 50 years.

Orphan School Creek, which originates in Sydney University and joins Johnstons Creek above Wigram Road, was turned into a stormwater channel between 1898 and 1938.

The Creek has a 500 hectare catchment, and it rises and falls with the tides. Sydney Water plans to naturalise Johnstons Creek in 2019, replacing the concrete with sandstone, and putting in native plants.

MANGROVES

There is a small group of mangroves on the foreshore near Chapman Road. Under the Bicentennial Park Stage 1 masterplan of 1987, the proposal was for a much larger area. But the Save Rozelle Bay group objected to the scale, arguing it would result in a major loss of open space. The final area is about one third of the original area proposed.

Planting the mangrove forest began in 2006.

The grey mangrove, Avicennia corniculatum, is so called because of the silvery-grey undersides of the leaves, which bear salt glands. It is very difficult to propagate. Professor Bill Alloway, from the University of Sydney, had some success with transplanting seedlings, but after the first year only 20 of the 200 seedlings planted had survived. One of his students had successfully planted mangroves, twenty years earlier, in front of the Anchorage, and that experience gave them heart.

Mangroves have pneumatophores, upright breathing roots, which take in oxygen at low tide, and allow the roots and shoots to survive inundation at high tide. They are essential to the survival of the plants, but are vulnerable to damage by people and dogs walking across the area.

The mangroves have survived several episodes of damage, and there have been supplementary plantings. There were massive germinations of seedlings in 2015 and 2016, spreading the plants across the whole area. (16)

Mangroves Rozelle Bay

HAROLD PARK

Harold Park used to be known as Allen’s Glen, Allen’s Bush or Frog’s Hollow.

Between 1878 and 1900 the low-lying part of Harold Park was reclaimed by the Allen family and an investment company, with most of the work done by theNSW Public Works Department. The cliffs were cut away for the tramsheds.

Most of the reclaimed land became open space, and in 1888 it was known as the Lille Bridge Electric Running Ground. Professional athletics and pony racing were held under some of the first electric lights in Sydney.

The ground was expanded again in 1900, and was used for Rugby League, greyhound racing and then trotting. It was renamed Harold Park in 1929. The last race was held at Harold Park in 2010. The land was sold to Mirvac for apartments, incorporating redevelopment of the Tramsheds. (17)

The tramsheds were known as the Rozelle Tram Depot, opening in 1904. It

ceased operation in 1958 when the Glebe line closed.

Amixed row plantation, including five Moreton Bay Figs, one Port Jackson Fig and three Lombardy Poplars mark the boundary of the former Tram Terminus yard, between the light rail and the Tramshed. According to the City of Sydney, “The group [of trees] possibly dates from the late Victorian period as part of the construction of the sheds. Although there are no individual specimens of note, the mixed group has significance at the local level in terms of its historic landmark qualities and social history.” (18)

Wetlands

WETLANDS

Along the sides of the Creek and near the mouth, a coastal saltmarsh, which is an endangered community, has been established. Samphires, native couch and New Zealand Spinach are flourishing.

The wetland between the Creek and Chapman Road was constructed in 2001.

It is a 0.2 hectare tidally-influenced saltmarsh system. It also receives storm water from Annandale. Two previously underground large diameter pipes were exposed, and a weir constructed to dam the freshwater that drained from the 12 to 14 hectare catchment.

It supports a range of estuarine plants. An area of bushland has been established on a small rise between the wetland and Chapman Road. The sites are distinguished from other indigenous/mostly indigenous plantings because they are maintained by volunteer groups or specialist bush regeneration contractors.

Most have been established and are maintained by two volunteer groups – the Glebe Bushcare Group, who have also propagated many of the species planted at these sites at the Rozelle Bay Community Native Nursery.

This area is still a work in progress. The City of Sydney 2013 Johnstons Creek Master Plan states “there are opportunities to improve the freshwater treatment by retaining the saltmarsh and extending this drainage system”.

“The topography and the location at the end point of the catchment area provide great opportunities for the parklands to serve an important ecological function in treating stormwater. The parklands also offer a great opportunity to extend the estuarine habitat that existed before the bay was filled. The concrete edges of the canal are just at the right height to allow minor inundation on high tides, and this creates a perfect environment for saltmarsh to grow.” (19)

PLANTS OF THE WETLAND AND COASTAL SALTMARSH

Avicennia marina var. australasica, Mangrove

Sarcocornia quinqueflora, Samphire or Beaded Glasswort

Suaeda australis, Austral Seablite

Samolus repens, Creeping Brookweed

Tetragonia tetragonioides, New Zealand Spinach

Lobelia alata, Lobelia

Zostera capricorni, Eel Grass or Ribbon Weed

Poa poiformis, Coastal Tussock Grass

Cyperus laevigatus, Sedge

Isolepsis nodosus, Sedge

Juncus kraussii, Sea Rush

Triglochin striata, Streaked Arrow Grass

Sporobolus virginicus, Sand couch

Schoenus apogon, Common bog-rush (20)

Estuarine vegetation, Johnstons Creek

ORPHAN SCHOOL CREEK

Parks and walkways along Johnstons Creek connect Bicentennial, Jubilee and Federal Parks with Orphan School Creek. The Creek joins Johnstons Creek just above Wigram Road near Booth Street. The Creek originates in the University of Sydney. The Creek was known locally as The Gully. It was piped by the Water Board in 1926.

Orphan School Creek is one of the most recent additions to the parklands of Glebe and Forest Lodge, and it is undoubtedly one of the most impressive.

The sale of the Children’s Hospital in 1995 opened up the possibility of restoring the Creek. Although the area was weedy and rubbishy, it provided good habitat for small birds like blue wrens and for frogs and reptiles. But most of it had to be cleared to enable soil remediation. The plan was to restore a bushland habitat using plants that had been locally indigenous.

The headline of the local paper, the Village Voice in November 1998 stated: ‘Bush Gully saved – but bulldozers must demolish first’.

Orphan School Creek is recognised for its high biodiversity values, and the astonishing regeneration of the bushland. A large number of plant species grow there, including what is possibly a survivor from pre-settlement days, an Angophorafloribunda or rough-barked apple. The tree is on the corner of the Wood Street playground, surrounded by planking to protect its roots.

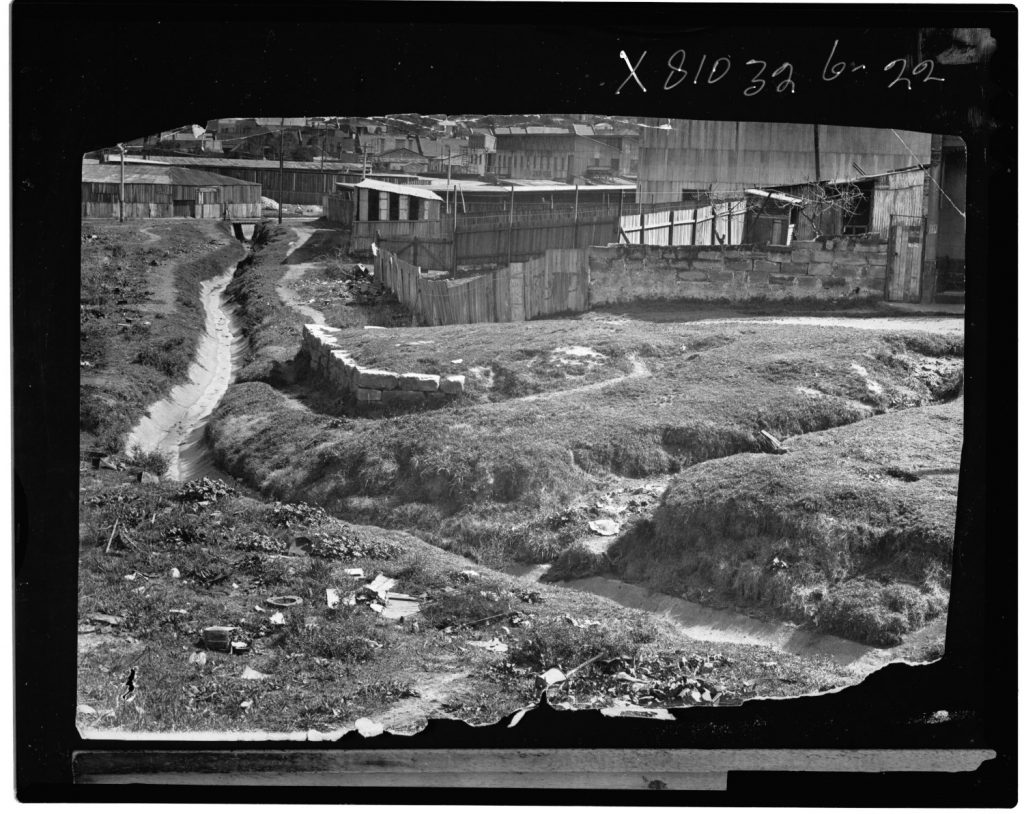

Orphan School Creek, looking NW towards Hereford Street, 1926

Negative X810326-22 Courtesy Sydney Water/ WaterNSW Historical Research Archive

Orphan School Creek, looking NW to Hereford Street, 2019

CREATING A BUSHLAND HABITAT AT ORPHAN SCHOOL CREEK

From Judy Christie

In 1995 the Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children moved to Westmead and the 4.5 hectare site was sold. The following year a local community group, FFROGS (Friends, Residents and Ratepayers of the Gully) formed, the Gully being Orphan School Creek. The group began monthly bird surveys to establish habitat values.

The group made a submission to the local council over the rezoning of the site, and argued for a 10 metre minimum open space buffer and 15m setback on Orphan School Creek to protect wildlife.

In 1999, the site owner, Sterling Estates, submitted plans to Leichhardt Council outlining the agreed habitat objectives and the intention to recreate the original vegetation communities. A ‘Whole Gully’ landscape concept was developed, but to do this there needed to be a land swap between Leichhardt Council and Westmead Children’s Hospital and agreement on land values.

But by the time Forest Lodge and Glebe came under the City of Sydney, in May 2003, there was still no progress on the Whole Gully vegetation, nor the land swap.

The following year stages 1 and 2 of the revegetation began on the sections owned by the developers and by Sydney Water, from Pyrmont Bridge Road to Hereford Street.

The plan was to replicate Sandstone Creek, Sandstone Forest and Turpentine-Ironbark Forest plant communities, with the plants grown from locally-collected seeds.

In 2007 plans were put together for the remediation and revegetation of the Wood Street land, with the options of either wildlife habitat or community gardens in the northern section. FFROGs supported the wildlife habitat, and so did the residents.

The third stage of revegetation was on the steep banks below Sterling Court, but problems with the soil and bank stabilisation lead to many species dying or failing to thrive. In 2008 the City of Sydney Council, despite earlier supporting the wildlife habitat proposal, introduced changes to the plan which included increasing the size of the playground, reducing the area of habitat, introducing exotic turf and creating a zig zag path up the eastern slope. Despite protests and community demonstrations against the zig zag path, which it was argued would lead to loss of habitat and create management problems, Council narrowly voted in its favour.

In 2012 the Friends of Orphan School Creek Bushcare group was formed. It conducts regular working bees and other events. The following year the City of Sydney took over management and maintenance of the revegetation area, and described it as the ‘largest bush restoration site’ in the City. (21

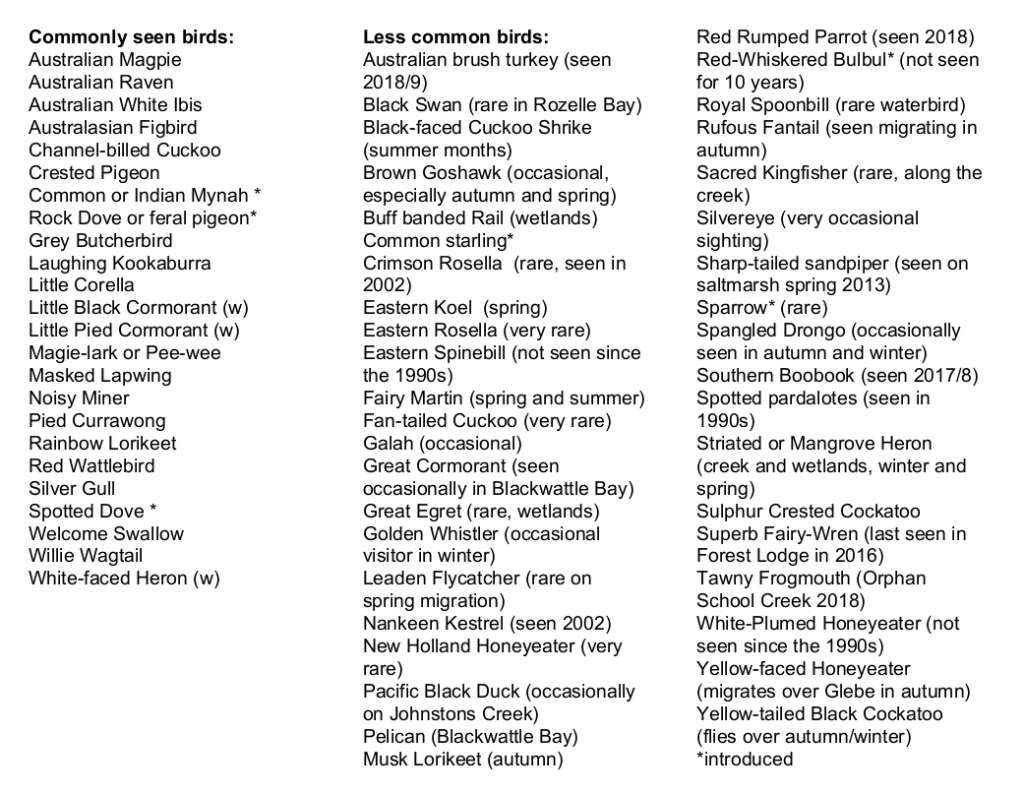

THE BIRDS OF GLEBE AND FOREST LODGE

The bird population of Glebe and Forest Lodge has changed over the past half century.A study comparing the pre-1900 bird population of Sydney with the bird community of 1998/9 found a shift in body size, with a decline in small insect-eating birds, and an increase in larger species.

None of the ten most commonly collected species of pre-1900 Sydney – including the Superb Fairy-wren, New Holland Honeyeater and Golden Whistlers – appeared one century later. Many other smaller birds once often seen in Glebe have not been sighted, or only rarely sighted, since the 1990s. These include Silvereyes, Spotted Pardalotes, the Eastern Spinebill and the White-Plumed Honeyeater.

The current list is dominated by the native birds Australian Magpie, Pied Currawong, Noisy Miner and Rainbow Lorikeet, and three exotic species (Common or Indian Myna, Rock Dove or feral pigeon and Spotted Dove).

Grey Butcherbirds, Kookaburras, Masked Lapwings, Noisy Miners, Pied Currawongs, Rainbow Lorikeets and Red Wattlebirds have been breeding in Glebe. The Blue Wren sub-committee of The Glebe Society is dedicated to restoring habitat for small birds. (22)

Bird List

TREES

* possibly natural occurring at site

Acacia implexa, Hickory Wattle*

Acacia parramattensis, Parramatta wattle*

Acmena smithii, Lilly Pilly

A. podalyriifolia,Queensland wattle

Allocasuarina littoralis, Black Sheoak

Angophora costata, Smooth-barked apple*

Banksia integrifolia, coast Banksia*

Banksia serrata, old man banksia

Casuarina cunninghamiana, River Oak

Casuarina glauca, Swamp oak

Corymbia citriodora, Lemon scented gum

Corymbia maculata, Spotted Gum

Cupaniopsis anacardiodes, Tuckeroo

Elaeocarpus reticulatus, Blueberry Ash

Eucalyptus botryoides, Bangalay*

E. saligna, Sydney Blue Gum

E. torelliana, Cadaghi

Ficus rubiginosa, Port Jackson Fig*

Leptospermum trinervium, Flaky-barked Tea-tree

Lophostemon confertus, Brush Box

Melaleuca bracteata, Black tea-tree

Melaleuca stypheloides,Prickly-leaved paperback

Notelaea longifolia, Mock Olive

Stenocarpus sinuatus, Firewheel Tree

Syncarpia glomulifera, Turpentine

Syzgium australe, Brush Cherry

Tristaniopsis laurina, Water Gum

SHRUBS

Acacia falcata, Sickle Wattle

A. floribunda, White Sally Wattle

A. linifolia, Flax wattle

A. terminalis, Sunshine Wattle

A. ulicifolia, Prickly Moses

Banksia aemula, Wallum Banksia

B. ericifolia, Heath Banksia

B. marginata, Silver Banksia

B. spinulosa, Hair-pin Banksia

Breynia oblongifolia, Coffee Bush

Callistemon citrinus, Crimson Bottlebrush

C. linearis, Narrow-leaved Bottlebrush

Correa alba, White Correa

Correa reflexa, Common Correa

Dodonaea triquetra, Large-Leaved Hop Bush

D. viscosa, Sticky hop bush

Doryanthese excelsa, Gymea Lily

Grevillea rosmarinifolia, Rosemary Grevillea

G. sericea, Pink Spider Flower

Hakea sericea, Needlebush

H. teretifolia, Needlebush

Kunzea ambigua, Tick Bush

K. capitata, Pink Kunzea

Leptospermum polygalifolium, Tantoon

Leucopogon parviflorus, Coastal Beard-heath

Melaleuca armillaris, Bracelet Honey-myrtle

M. ericifolia, Swamp Paperbark

M. nodosa, Prickly-leaved Paperbark

Myoporum insulare(probably), Boobialla

Ozothamnus diosmifolius, Dogwood

Philotheca myoporoides, Long-leaved Wax Flower

Westringia fruticosa, Native Rosemary

HERBS

Carpobrotus galaucescens, Coastal pigface*

Chenopodium glaucum, Glaucous Goosefoot*

Commelina cyanea, Scurvy weed*

Centella asiatica, Pennywort*

Dianella caerulea, Blue Flax Lily

D. revoluta, Blue Flax Lily

Dichondra repens, Kidney Weed

Geranium homeanum, Native Geranium

Pelargonium australe, Native Pelargonium

Plectranthus parviflorus, Cockspur flower

Portulaca oleracea, Pigweed*

Pratia purpurascens, Whiteroot

Sarcocornia quinqueflora, Beaded Glasswort*

Suaeda australis, Austral Seabite*

Tetragonia tetragonioides, New Zealand Spinach*

Triglochin striata, Streaked Arrow Grass*

Wahlenbergia gracilis, Native Blue Bell*

CLIMBERS

Cissus antarctica, Kangaroo Vine

Commelina cyanea, Scurvy weed

Eustrephus latifolius, Wombat berry

Geitonoplesium cymosum, Scrambling lily

Glycine microphylla, –

G. tabacina, –

Hibbertia scandens, Climbing Guinea Flower

Pandorea pandorana, Wonga Wonga Vine

GRASSES, SEDGES, RUSHES

Austrodanthonia species, Wallaby grass

Austrostipa ramosissima, Speargrass

Cymbopogon refractus, Barb wire grass

Cyperus gracilis,Slender Flat-sedge*

Cyperus mirus, Cyperus*

Dichelachne crinita, Longhair plumegrass

Dichelachne micrantha, Shorthair plumegrass*

Echinopogon caespitosus, Hedgehog grass

E.n ovatus, Hedgehog grass

Ficinia nodosa, Knotted Club-rush

Gahnia aspera, Rough Saw-sedge

Juncus kraussii, Sea rush

J. usitatus, Common rush

Lachnagrostis avenacea, Blowngrass

Lomandra hystrix, Mat-rush

Lomandra longifolia, Rush

Microlaena stipoides, Weeping grass

Oplismenus aemulus, Basket Grass*

Sporobolus virginicus,Saltwater Couch

Themeda australis, Kangaroo Grass (23)

REFERENCES

1. Doug Benson and Jocelyn Howell, Taken for Granted, The Bushland of Sydney and its Suburbs. Kangaroo Press, 1995

2. Paul Irish and Tamike Goward, Blackwattle Creek, Barani, Sydney’s Aboriginal History. https://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/blackwattle-creek/

3. Max Solling, Grandeur and Grit, Halstead Press, 2007

4. City of Sydney, https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/vision/better-infrastructure/parks-and-playgrounds/completed-projects/glebe-foreshore

5. East Glebe Foreshore Plan of Management https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/138756/GlebeForeshoreEastPoM_adopted.pdf

6. Glebe’s waterfront History, the last 40 years, John Buckingham, 2008.

7. The Glebe Society, https://www.glebesociety.org.au/publications/bulletin/old-bulletins-page/ 8. Urban Ecology Strategic Action Plan https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/198821/2014-109885-Plan-Urban-Ecology-Strategic-Action-Plan_FINAL-_adopted.pdf

9. https://trees.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au

The City of Sydney Significant Trees register

10. Glebe’s waterfront History, the last 40 years, John Buckingham, 2008.

11. ibid

12. https://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fishing/recreational/fishing-skills/fishing-in-sydney-harbour

14. https://sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2018/09/27/oyster-research-aims-to-clean-the-water-of-sydney-harbour.html15. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/researchpapers/Documents/pollution-in-sydney-harbour-sewage-toxic-chemica/Pollution%20in%20Sydney%20Harbour.pdf

16. Tony Larkum, The Mangrove plantings on Rozelle Bay https://www.glebesociety.org.au/wp-content/uploads/bulletins/2007_03.pdfabd https://www.glebesociety.org.au/wp-content/uploads/bulletins/2017_07.pdf

17. Harold Park, A history. Susan Marsden assisted by Max Solling. 2016

18. The City of Sydney Significant Trees register

19.City of Sydney 2013 Johnstons Creek Master plan Report

20. https://ramin.com.au/annandale/wetlands.shtml

21. Judy Christie, personal communication

22. Avifauna surveys, City of Sydney spring 2016, autumn 2017

23. Urban Ecology Strategic Action Plan https://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/198821/2014-109885-Plan-Urban-Ecology-Strategic-Action-Plan_FINAL-_adopted.pdf